Because Princeton Books has a suggestion!

No serious birder can have too many references from Steve Howell. I think this is at least the 3rd that I own and I feel that his style is transitioning. While Gulls of the Americas is a must-have reference, a lot of the text is in chapters of fairly dense description at the end of the book. This book is much more Sibley meets Crossley with every page dominated by pictures, usually with text at the bottom of the page, and at times annotated with Peterson like arrows.

Here's a sample for Parasitic Jaeger...

But it doesn't just cover birds we find now and then, it covers everything from all the penguins to all the albatrosses to all the storm petrels to all the boobies to ... you get the idea.

One of the best things about this book is that while overall the format is somewhat like Sibley (with photos instead of watercolors) with an intro plate showing small images of all the species in a grouping and then going into each individually with its own page more or less, he changes things up where necessary. If he needs to depart from that format to do a specific comparison of a given set of birds he does. Here's an example

Seabirds are incredibly complex and not everything is yet known with regards to aging and taxonomy; the authors do a good job of laying out where uncertainties lie.

I would recommend this book to anyone who is going to be spending time on the ocean. The photographs are excellent (apologies for the low quality reproductions here) and I think should give a person a reasonable gestault foundation from which to build in the specific points that the authors highlight.

And full disclosure, I got a free copy for writing a review! (though I've never seen any evidence that Princeton reviews the reviews).

Showing posts with label Book reviews. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Book reviews. Show all posts

Thursday, December 19, 2019

Wednesday, January 9, 2019

Need one last present?

Or have some credit from returning the knickknacks and chotzkis that you showed up in your stocking? Well, here is the latest from Princeton Press (pics of my free review copy)...

I was fairly intrigued by this book. I very much enjoyed Pete Dunne's Hawks in Flight, a book written in chapter style that relies as much on the description to create an image of the bird as it does the illustrations, probably more so than any identification book I've encountered. In this day and age of SLR photos however, it's unlikely many bird books will ever be as successful as that one with it's huge ratio of words to pics.

This book tries to encompass some of the description, while still showing pics of most ages of most of the species. Dunne italicizes a lot of the pearls and key points in many of the paragraphs and I think that brings out his style when he does. When he isn't italicizing it feels like it bogs down somewhat and becomes more general.

Here's a sample page...

The photographs that are chosen are excellent, but sometimes feel a little random which I think is because they're essentially all Karlson's photos. For example, in the Sabine's Gull chapter they spend a couple paragraphs discussing one of Karlson's photos that was also in Howell and Dunn's gull book with regards to aging. I don't see any way this discussion takes place if Karlson isn't overwhelmingly accounting for the photos.

If you're looking to finally take the plunge and learn the gulls, it's a lot more readable than either the Howell and Jon Dunn book or the even more ponderous Olson and Larsson. If you already have 2 or 3 gull specialty guides on your shelf, I'm not as sure this is going to add as much.

One significant drawback in my mind is that the authors spend very little time on potential rarities. I recognize that the chance that any of us is going to find a Slaty-backed Gull isn't particularly high, but I would have given that species an equal amount of content as the common North American ones since a lot of more advanced birders are going to be looking for them.

There is a quiz section in the back of the book which is fairly entertaining. I don't like that they don't give the location of the quiz photos however. Withholding that piece of info feels at odds with their goal of focusing on the regularly occurring species.

Overall this is a well-done book and I think a lot of people who want to tackle learning the gulls will find it exceedingly helpful.

I was fairly intrigued by this book. I very much enjoyed Pete Dunne's Hawks in Flight, a book written in chapter style that relies as much on the description to create an image of the bird as it does the illustrations, probably more so than any identification book I've encountered. In this day and age of SLR photos however, it's unlikely many bird books will ever be as successful as that one with it's huge ratio of words to pics.

This book tries to encompass some of the description, while still showing pics of most ages of most of the species. Dunne italicizes a lot of the pearls and key points in many of the paragraphs and I think that brings out his style when he does. When he isn't italicizing it feels like it bogs down somewhat and becomes more general.

Here's a sample page...

The photographs that are chosen are excellent, but sometimes feel a little random which I think is because they're essentially all Karlson's photos. For example, in the Sabine's Gull chapter they spend a couple paragraphs discussing one of Karlson's photos that was also in Howell and Dunn's gull book with regards to aging. I don't see any way this discussion takes place if Karlson isn't overwhelmingly accounting for the photos.

If you're looking to finally take the plunge and learn the gulls, it's a lot more readable than either the Howell and Jon Dunn book or the even more ponderous Olson and Larsson. If you already have 2 or 3 gull specialty guides on your shelf, I'm not as sure this is going to add as much.

One significant drawback in my mind is that the authors spend very little time on potential rarities. I recognize that the chance that any of us is going to find a Slaty-backed Gull isn't particularly high, but I would have given that species an equal amount of content as the common North American ones since a lot of more advanced birders are going to be looking for them.

There is a quiz section in the back of the book which is fairly entertaining. I don't like that they don't give the location of the quiz photos however. Withholding that piece of info feels at odds with their goal of focusing on the regularly occurring species.

Overall this is a well-done book and I think a lot of people who want to tackle learning the gulls will find it exceedingly helpful.

Monday, October 29, 2018

Birds of Central America

Want to get ahead on your Christmas shopping? Because if you're in the market for a present for someone who will go (or honestly has gone) to Central America I've got your answer (in the latest of offerings from Princeton Press who kindly provided me a free review copy):

The book, about the size and weight of big Sibley is in my opinion the best book I've ever seen for Neotropic birds, in this case Central America (which for this book excludes Mexico). But while I've never been to Guatamala or Nicaragua (and may never get to those places), it's really nice to have those birds in this book.

The book is laid out in what I would consider to be the traditional field guide fashion with maps and description facing the birds

The illustrations are really well done. It's not easy to capture the gestault of a bird, but this illustrator (I assume Dale Dyer) succeeds, which is no easy task with some of the weird neotropic flycatchers that just don't look like anything else. But since not everyone here has had the joys of seeing flatbills and elaenias I included a plate here that shows one of our spring heralds that every knows well.

My photos aren't as sharp as replications of these plates deserve, and apologies for the glare.

I've immensely enjoyed just flipping through the book because the illustrations are really accurate, and bring back memories of seeing these species whose names start to run together after a while.

I did have a couple of quibbling points with the book:

- The upper right hand corner of the plate has a number which represents how close to life size the illustrations are. Overly accurate calculations amuse me and I don't really buy that every bird is exactly 19% of life size or 23% or 58% as those numbers would apply; I would have rounded those off.

- The descriptions start with an overview of the range, at times this gets really into the weeds with lists of locations where uncommon or rare birds were seen. You wouldn't know from the text that the Darien of eastern Panama is the best place to go to see a Harpy Eagle; instead the book lists places where it's been seen (including the relevant literature citations!) which would probably be better placed in a summary book rather than a field guide. The pips included on the range map which pertain to those records are similar size to the little area you can hopefully expect to be shown one prospectively. Sibley does a better job of separating vagrant records from core range in his book.

- I would have saturated the illustrations a tad more; maybe that's just a result of eyes that grew up on the best Eastern Peterson edition and then have mostly looked at Sibley plates since, but the figures could pop even more.

- Taxonomy gets confusing as anyone who has tried to compare eBird checklists with older field guides. In situations where there have been recent splits or lumps the author places a superscript number that refers to an addendum at the end of the book explaining the split or the lump. I would have placed those in the text, or at least included a line (National Geo style) stating "formerly known as ..." to make it easier to figure out which names goes to what bird.

Thursday, June 21, 2018

Forget Father's Day?

Need a last second gift idea for the summer doldrums?

Can I suggest to you a latest offering from Princeton Press (who gave me a free copy to review)?

Why go out into the summer heat when you can bring photo subjects to you? (Some assembly required).

The first 3rd of the book is a review of butterfly biology basics, range maps for some of the common showy species with information on their food plant as both adults and caterpillars. There's intro information about the different families of butterflies and short accounts for some of the most common and widespread species. A lot of it is going to be duplicated if you already have Kaufman's (or a similar) butterfly field guide.

For birders probably there's more new information about the plants, which is the subject for the middle third of the book. Did you know some flowers produce only pollen and no nectar? The spiderwort I plant every few years will attract bees ... but no butterflies since they require the nectar.

Of course the book is chock full of eye candy photos.

The final third focuses on specific regions (Northwest, California, Plains, Midwest, Northeast, and Florida) to give more targeted recommendations about different plants.

There's a lot of information in this book. Honestly I would probably have included some specific layouts of things to plant for both small and medium sized plots and made it more obvious about the sun and shade requirements of the plants. Practically I think I would be more likely to try this if the book tried to give me less overall information. Personally I'd prefer more exact directions for example gardens that could be adapted to one's space rather than having all the information and then having to internalize it and come up with a plan.

In any case, the book is going on the shelf and I look forward to experimenting in the future.

Can I suggest to you a latest offering from Princeton Press (who gave me a free copy to review)?

Why go out into the summer heat when you can bring photo subjects to you? (Some assembly required).

The first 3rd of the book is a review of butterfly biology basics, range maps for some of the common showy species with information on their food plant as both adults and caterpillars. There's intro information about the different families of butterflies and short accounts for some of the most common and widespread species. A lot of it is going to be duplicated if you already have Kaufman's (or a similar) butterfly field guide.

For birders probably there's more new information about the plants, which is the subject for the middle third of the book. Did you know some flowers produce only pollen and no nectar? The spiderwort I plant every few years will attract bees ... but no butterflies since they require the nectar.

Of course the book is chock full of eye candy photos.

The final third focuses on specific regions (Northwest, California, Plains, Midwest, Northeast, and Florida) to give more targeted recommendations about different plants.

There's a lot of information in this book. Honestly I would probably have included some specific layouts of things to plant for both small and medium sized plots and made it more obvious about the sun and shade requirements of the plants. Practically I think I would be more likely to try this if the book tried to give me less overall information. Personally I'd prefer more exact directions for example gardens that could be adapted to one's space rather than having all the information and then having to internalize it and come up with a plan.

In any case, the book is going on the shelf and I look forward to experimenting in the future.

Saturday, January 27, 2018

Far From Land

What better way to slowly work my way back into blogging than a book review?

This one is FAR FROM LAND, The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds, by Michael Brooks.

Let's talk about what this book is. What it is is an about 200 page review of Seabird Biology divided into 10 chapters on topics such as migration, breeding biology, feeding habits, etc. It focuses mainly on tubenoses, penguins, auks, and pelagic terns; basically colony nesters who feed out in the ocean.

Seabirds are difficult birds to study for obvious reasons, but there has been a huge expansion of knowledge over the last decade or so thanks to miniaturization of tracking devices. This book summarizes many of these papers in very readable prose. Did you know frigatebirds can sleep with one side of their brain at a time (and occasionally both sides!) while flying? Do you want to learn about Ashmole's Halo and how it applies to the distance birds can reach feeding areas from their colonies? This book is a wealth of information giving background on a set of birds we don't know a ton about.

What it isn't is an identification guide. There's also fairly limited illustration. My honest guess is that sales of this book would be doubled with photographic eye candy. It's mostly illustrated with well-done black and white drawings, as well as figures showing migration tracks of tagged birds and the like. That being said I'm sure that cost would go up with a ton of glossy color photos as well; clearly the publishers felt this was the best marriage between information and shelf appeal.

Who is interested in this book? Any birder who's working their way through slow winter months may enjoy reading a section of a chapter and getting a little birding fix, especially if they are interested in learning more about birds rather than just passively looking at them. It definitely should appeal to the birder who is planning on a pelagic and wants to be able to put the birds in better context than just ticks on a list.

This book will be available for purchase in March; Princeton Press provided me a review copy.

This one is FAR FROM LAND, The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds, by Michael Brooks.

Let's talk about what this book is. What it is is an about 200 page review of Seabird Biology divided into 10 chapters on topics such as migration, breeding biology, feeding habits, etc. It focuses mainly on tubenoses, penguins, auks, and pelagic terns; basically colony nesters who feed out in the ocean.

Seabirds are difficult birds to study for obvious reasons, but there has been a huge expansion of knowledge over the last decade or so thanks to miniaturization of tracking devices. This book summarizes many of these papers in very readable prose. Did you know frigatebirds can sleep with one side of their brain at a time (and occasionally both sides!) while flying? Do you want to learn about Ashmole's Halo and how it applies to the distance birds can reach feeding areas from their colonies? This book is a wealth of information giving background on a set of birds we don't know a ton about.

What it isn't is an identification guide. There's also fairly limited illustration. My honest guess is that sales of this book would be doubled with photographic eye candy. It's mostly illustrated with well-done black and white drawings, as well as figures showing migration tracks of tagged birds and the like. That being said I'm sure that cost would go up with a ton of glossy color photos as well; clearly the publishers felt this was the best marriage between information and shelf appeal.

Who is interested in this book? Any birder who's working their way through slow winter months may enjoy reading a section of a chapter and getting a little birding fix, especially if they are interested in learning more about birds rather than just passively looking at them. It definitely should appeal to the birder who is planning on a pelagic and wants to be able to put the birds in better context than just ticks on a list.

This book will be available for purchase in March; Princeton Press provided me a review copy.

Wednesday, June 21, 2017

The New Neotropical Companion

It's been a long time since I've done a book review, but the doldrums of summer are conducive to armchair birding so I present to you The New Neotropical Companion by John Kricher. If you're planning on spending any time in Central America south of Mexico or the northern 2/3 of South America this book will definitely enrich your experience and enhance your understanding of what you're seeing in unfamiliar ecosystems.

It's not an easy book to summarize since it covers a lot more ground than your typical field guide. Physically it's about 8x10 inches and just over 400 pages thick. I opened the book mostly at random to take the page views so you can get a sense of what the book looks like on the inside. The photos are sharply focused and pleasing to look at; don't judge them on my reproductions. There's a few places where I have a better photo of the subject, the other 98-99% of the time the book wins.

A chapter index would have been nice to include. The first 6 chapters discuss basics of rainfall, soil ecology, plant diversity and the like. Chapter 7 is a nice discussion of plant succession which brings to life both different field studies the author wants to highlight as well as the more basic background information. Chapters 8-11 discuss speciation, evolution, co-evolution, and species diversity. What is more interesting about the neotropics than the incredible diversity of species? This section talks about how it all came to be.

Chapters 12-14 discuss specific ecosystems, divided into wet, high elevation, and dry sections. It looks at specific plants, animals, and (predominantly) birds that are unique, characteristic, or simply an interesting element of their diverse surroundings.

Chapter 15 (the longest chapter at about 60 pages) takes the birds family by family and is richly illustrated of course. Chapter 16 deals with the mammals, herps, and insects. Chapter 17 focuses on human interaction with the rain forest.

The bottom line is that if you are going to the neotropics, there's a ton of information here that your guide is likely not going to have time to discuss (or know); you will enjoy your trip more even if you just thumbing through this book and reading it little paragraphs or sections at a time.

And the requisite disclaimer: Princeton sent me a free review copy of the book though they've never asked to see what I wrote about it.

It's not an easy book to summarize since it covers a lot more ground than your typical field guide. Physically it's about 8x10 inches and just over 400 pages thick. I opened the book mostly at random to take the page views so you can get a sense of what the book looks like on the inside. The photos are sharply focused and pleasing to look at; don't judge them on my reproductions. There's a few places where I have a better photo of the subject, the other 98-99% of the time the book wins.

A chapter index would have been nice to include. The first 6 chapters discuss basics of rainfall, soil ecology, plant diversity and the like. Chapter 7 is a nice discussion of plant succession which brings to life both different field studies the author wants to highlight as well as the more basic background information. Chapters 8-11 discuss speciation, evolution, co-evolution, and species diversity. What is more interesting about the neotropics than the incredible diversity of species? This section talks about how it all came to be.

Chapters 12-14 discuss specific ecosystems, divided into wet, high elevation, and dry sections. It looks at specific plants, animals, and (predominantly) birds that are unique, characteristic, or simply an interesting element of their diverse surroundings.

The bottom line is that if you are going to the neotropics, there's a ton of information here that your guide is likely not going to have time to discuss (or know); you will enjoy your trip more even if you just thumbing through this book and reading it little paragraphs or sections at a time.

And the requisite disclaimer: Princeton sent me a free review copy of the book though they've never asked to see what I wrote about it.

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Who needs a last second gift idea?

If so, then the Offshore Sea Life ID Guide may be for you! Fair warning, Princeton Press sent me a free review copy. This one deals just with the East Coast.

I was ill-prepared from a sea-sickness standpoint for the pelagic we did this last summer. I would expect that by the time next spring rolls around I'll have forgotten the depths of misery that I (couldn't quite) stomach and will be willing to re-try it. Written by Steven Howell and Brian Sullivan, it's more of a handbook, checking in at a mere 64 pages. The first 10 or so are intros, the next 10-15 pages deal with whales. Pelagic birds account for pages 26-50. Here's a sample plate.

Basically it's a cross between Sibley and Crossley, using Sibley's format but with pics. It wouldn't surprise me if this approach becomes pretty standard in field guides moving forward.

There's another 5 pages on flying fish which I would certainly have appreciated on our pelagic; we saw a good number of flying fish and I would have liked to have known more about them.

Finally the book deals with some of the billfish, rays, and sharks that are possibilities to encounter.

The book is a fun mix of fairly targeted plates dealing with some difficult to identify birds along with more general info about some of the other sealife that could be encountered on a pelagic. While I was surprised when I received it how short the book is, the small size will definitely increase it's usability in the field. At $14.95, I think this is a worthwhile investment for a birder planning to return to the Atlantic seas.

I was ill-prepared from a sea-sickness standpoint for the pelagic we did this last summer. I would expect that by the time next spring rolls around I'll have forgotten the depths of misery that I (couldn't quite) stomach and will be willing to re-try it. Written by Steven Howell and Brian Sullivan, it's more of a handbook, checking in at a mere 64 pages. The first 10 or so are intros, the next 10-15 pages deal with whales. Pelagic birds account for pages 26-50. Here's a sample plate.

Basically it's a cross between Sibley and Crossley, using Sibley's format but with pics. It wouldn't surprise me if this approach becomes pretty standard in field guides moving forward.

There's another 5 pages on flying fish which I would certainly have appreciated on our pelagic; we saw a good number of flying fish and I would have liked to have known more about them.

Finally the book deals with some of the billfish, rays, and sharks that are possibilities to encounter.

The book is a fun mix of fairly targeted plates dealing with some difficult to identify birds along with more general info about some of the other sealife that could be encountered on a pelagic. While I was surprised when I received it how short the book is, the small size will definitely increase it's usability in the field. At $14.95, I think this is a worthwhile investment for a birder planning to return to the Atlantic seas.

Tuesday, September 22, 2015

Van Perlo's Birds of South America - Passerines

The latest installment of book reviews for Princeton Press who graciously provided me a review copy...

South American, the Bird Continent. Who doesn't aspire to eventually go (or return there)? This book contains every flycatcher, manakin, antwhatever, swallow, tanager, along with tapaculos, tityras, and donacobiuses (though it turns out there's only one donacobius, so I guess we don't need to worry about whatever the plural is). And lots more. 1900-2000 species are illustrated in a book about the size of an Eastern Peterson (though with 400 birds it's a little thicker) on a little less than 200 plates, with brief info about each species on the facing page.

Let's open it, shall we? To some random page, how about 314?

Immediately reality sets in for a book that needs to illustrate nearly 2000 species in a small format. The artwork is functional (and is better than this reproduction indicates), but the birds are going to be relatively small and there won't be the rich 3 dimensional appearance that's in the modern Peterson or quite as clean as Sibley. That being said, it's painted by a single artist which allows a person to get their eye in easier to adjust to how that artist interprets the birds. I've actually seen 2 birds on that plate (#4, the Golden-hooded Tanager, a widely distributed neotropic bird, and #8, Speckled Tanager, a bird I don't have as good a photo of). Here's Golden-hooded from Costa Rica a few years ago

Though it's probably easier to judge using birds we're all familiar with

I think the shapes are excellent on the Blue Grosbeak and Indigo Buntings, reasonable for the Ovenbird and Golden-wing, though the Blue-wing and Tennessee are a little fat, and the Parula a little long. That being said, I think they do give an accurate impression of what these birds look like, something that the Garrigues books for Costa Rica and Panama that I've studied a lot the last few years can occasionally leave to be desired.

However, this book isn't really a field guide. While it does give some concise information about the bird's identification, its habitat and voice, and the book is small, I don't think anyone would carry it in the field given that the overwhelming majority of the birds aren't going to be possible in any given region. What it is, is an excellent (and at $22 on amazon a very economic) reference book for the armchair birder. While many of us have a few (or more) field guides to various regions (I think I have 5-6 for Central America and 1 for Equador), this helps give a much broader picture of bird distribution (and species possibilities). A person can see what overlap occurs between Colombia, Equador, and Peru, or what parts of Brazil would give a reasonable sampling of its birds.

Want to know how many attilas there are?

This book will tell you (seven).

Want to stare at (one of 5 1/2 plates) of Antpittas that you're realistically only going to see on paper? No problem.

Bottom line, this book is very worth the price for anyone who would like to consider travel to the birdiest continent in the world.

South American, the Bird Continent. Who doesn't aspire to eventually go (or return there)? This book contains every flycatcher, manakin, antwhatever, swallow, tanager, along with tapaculos, tityras, and donacobiuses (though it turns out there's only one donacobius, so I guess we don't need to worry about whatever the plural is). And lots more. 1900-2000 species are illustrated in a book about the size of an Eastern Peterson (though with 400 birds it's a little thicker) on a little less than 200 plates, with brief info about each species on the facing page.

Let's open it, shall we? To some random page, how about 314?

Immediately reality sets in for a book that needs to illustrate nearly 2000 species in a small format. The artwork is functional (and is better than this reproduction indicates), but the birds are going to be relatively small and there won't be the rich 3 dimensional appearance that's in the modern Peterson or quite as clean as Sibley. That being said, it's painted by a single artist which allows a person to get their eye in easier to adjust to how that artist interprets the birds. I've actually seen 2 birds on that plate (#4, the Golden-hooded Tanager, a widely distributed neotropic bird, and #8, Speckled Tanager, a bird I don't have as good a photo of). Here's Golden-hooded from Costa Rica a few years ago

Though it's probably easier to judge using birds we're all familiar with

I think the shapes are excellent on the Blue Grosbeak and Indigo Buntings, reasonable for the Ovenbird and Golden-wing, though the Blue-wing and Tennessee are a little fat, and the Parula a little long. That being said, I think they do give an accurate impression of what these birds look like, something that the Garrigues books for Costa Rica and Panama that I've studied a lot the last few years can occasionally leave to be desired.

However, this book isn't really a field guide. While it does give some concise information about the bird's identification, its habitat and voice, and the book is small, I don't think anyone would carry it in the field given that the overwhelming majority of the birds aren't going to be possible in any given region. What it is, is an excellent (and at $22 on amazon a very economic) reference book for the armchair birder. While many of us have a few (or more) field guides to various regions (I think I have 5-6 for Central America and 1 for Equador), this helps give a much broader picture of bird distribution (and species possibilities). A person can see what overlap occurs between Colombia, Equador, and Peru, or what parts of Brazil would give a reasonable sampling of its birds.

Want to know how many attilas there are?

This book will tell you (seven).

Want to stare at (one of 5 1/2 plates) of Antpittas that you're realistically only going to see on paper? No problem.

Bottom line, this book is very worth the price for anyone who would like to consider travel to the birdiest continent in the world.

Wednesday, December 17, 2014

the Beetle book

Looking for that last minute gift idea? (Of course not, it's not December 23rd yet is it?) But if you were, what better idea than a fine selection from Princeton Books who are willing to provide review copies to blogging shills?

I've really enjoyed the Dragonfly book, I have focused more on Odes the last couple summers than I have birds. With that in mind, Beetles of Eastern North America.

I had no idea how many of them there are. There's a mere 115 families known from the region. The book estimates that 20% of all life forms (including plants) are a beetle of some form. With that in mind, it covers about 1400 bugs, many of them without a common name. They state that 1400 represents about 10% of the possibilities. It's a fairly heavy ~550 page book.

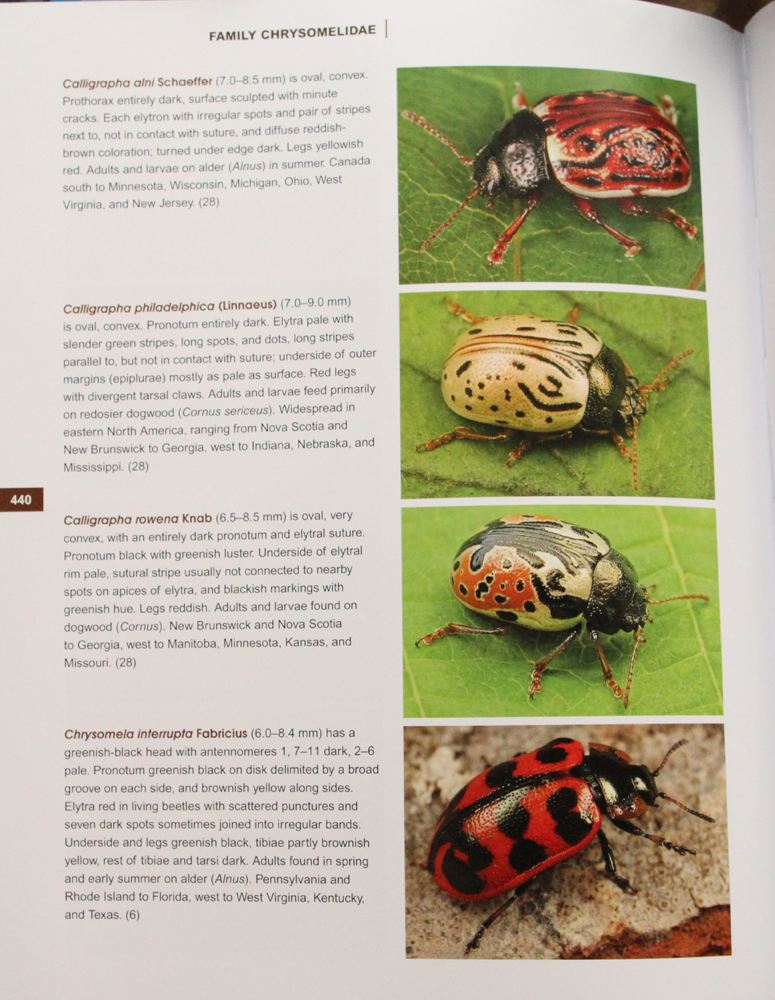

This is the layout, a page of fairly attractive things in the ladybug group

There's a nice intro describing strategies to find and attract beetles, not all of which are intuitive.

There's also a nice key to putting a bug into a general family; I would have appreciated something like this in the dragonfly book where I was essentially just page-whacking, thumbing through the book more or less at random trying to stumble onto the next section. They also include a ruler on the inside of the front and back cover, the lack of which was also a big critique I had of the dragonfly book. Somewhat disconcertingly, that ruler goes up to 7 inches (!).

I'm not sure that birders are the ideal target audience, dragonflies and butterflies are an easier leap. I think a person as interested in natural history in general may be more likely to embrace this menagerie.

I've really enjoyed the Dragonfly book, I have focused more on Odes the last couple summers than I have birds. With that in mind, Beetles of Eastern North America.

I had no idea how many of them there are. There's a mere 115 families known from the region. The book estimates that 20% of all life forms (including plants) are a beetle of some form. With that in mind, it covers about 1400 bugs, many of them without a common name. They state that 1400 represents about 10% of the possibilities. It's a fairly heavy ~550 page book.

This is the layout, a page of fairly attractive things in the ladybug group

There's a nice intro describing strategies to find and attract beetles, not all of which are intuitive.

There's also a nice key to putting a bug into a general family; I would have appreciated something like this in the dragonfly book where I was essentially just page-whacking, thumbing through the book more or less at random trying to stumble onto the next section. They also include a ruler on the inside of the front and back cover, the lack of which was also a big critique I had of the dragonfly book. Somewhat disconcertingly, that ruler goes up to 7 inches (!).

I'm not sure that birders are the ideal target audience, dragonflies and butterflies are an easier leap. I think a person as interested in natural history in general may be more likely to embrace this menagerie.

Friday, April 4, 2014

Rare Birds of North America review

The latest of the intermittent advertisements, errrrrr, reviews for Princeton Books (who provided a free review copy).

I think this is my favorite bird book that I've received from Princeton (the dragonfly book passed the test that I bought one myself when I'd promised the review copy to someone else and ended up having to own it after looking at it). As the name implies it covers North American rarities, specifically 262 species that have generally occurred less than 5 times in North America. The book has extensive discussion about patterns of vagrancy and occurrence, which I expected. What I didn't expect was excellent identification discussion (I probably should have given that Steve Howell is the lead author) and even better illustrations.

Here's the Lesser Sand-plover plate; this would have been very helpful last fall when the bird appeared in Indiana and I was kind of stretching on a resource that would eliminate Greater.

The illustrations (apologies for my photographs of them) are better than Sibley's (more on him later). My only criticism of them is that the artist's (Ian Lewington's) style is to paint most of the birds in a fluffed relaxed affect; the shapes are a little off from what the bird's typically show. That being said, with just one painter, you can kind of get your eye in for how they're pictured and how they're likely to look in life. Here's plates of 2 of the birds I have seen recently, Green Violet-ear,

(Note in the Violet-ear plate the comparison with a Ruby-throat; the book commonly will show the rarity next to the regular bird it most resembles or would be encountered with. It reminds me of the European Collins Guide in this manner.)

and Cinnamon Hummingbird.

The problem this book has is its timing. It reminds me a lot of 10-15 years ago when Kaufman and Sibley came out with their field guides within a few weeks of each other. They claimed there was no competition since Kaufman was billed as a replacement for Peterson and Sibley as a replacement for the National Geo. The problem was that Sibley didn't include the rarities. Illustrations of the Aleutian, pelagic, or southern border state rarities remained only in National Geo or specialty guides. Sibley replaced Peterson, Kaufmann was an afterthought, and National Geo with all of its problems retained at least some of its niche.

This book was supposed to come out a year ago. I'm not sure what the delay was, but now it's being released about the same time as the new Sibley which now contains illustrations of a lot of these same birds. The question is how many birders are going to get this book when the new Sibley covers most of them at least in passing. I think I've seen exactly 3 birds from the book in the ABA area and unless I move to SE Arizona my odds of discovering one on my own is close to nil. Unless you're birding the Alaskan islands, doing a lot of pelagics, or living in one of the border regions (or conceivably even California) this book is of academic interest, really nicely done, but may not have that much practical use. Off Amazon this book is $20-25, the dust jacket says $35. Honestly though, this book is certainly worth owning at that price even if my Midwestern readers are probably only going to be chasing (or dreaming) about these birds. If you've got a family of 4 you can't get out of Panera Bread without spending more that that.

Want others' opinions? Here's Cory Gregory and Jerry Jourdan.

I think this is my favorite bird book that I've received from Princeton (the dragonfly book passed the test that I bought one myself when I'd promised the review copy to someone else and ended up having to own it after looking at it). As the name implies it covers North American rarities, specifically 262 species that have generally occurred less than 5 times in North America. The book has extensive discussion about patterns of vagrancy and occurrence, which I expected. What I didn't expect was excellent identification discussion (I probably should have given that Steve Howell is the lead author) and even better illustrations.

Here's the Lesser Sand-plover plate; this would have been very helpful last fall when the bird appeared in Indiana and I was kind of stretching on a resource that would eliminate Greater.

The illustrations (apologies for my photographs of them) are better than Sibley's (more on him later). My only criticism of them is that the artist's (Ian Lewington's) style is to paint most of the birds in a fluffed relaxed affect; the shapes are a little off from what the bird's typically show. That being said, with just one painter, you can kind of get your eye in for how they're pictured and how they're likely to look in life. Here's plates of 2 of the birds I have seen recently, Green Violet-ear,

(Note in the Violet-ear plate the comparison with a Ruby-throat; the book commonly will show the rarity next to the regular bird it most resembles or would be encountered with. It reminds me of the European Collins Guide in this manner.)

and Cinnamon Hummingbird.

The problem this book has is its timing. It reminds me a lot of 10-15 years ago when Kaufman and Sibley came out with their field guides within a few weeks of each other. They claimed there was no competition since Kaufman was billed as a replacement for Peterson and Sibley as a replacement for the National Geo. The problem was that Sibley didn't include the rarities. Illustrations of the Aleutian, pelagic, or southern border state rarities remained only in National Geo or specialty guides. Sibley replaced Peterson, Kaufmann was an afterthought, and National Geo with all of its problems retained at least some of its niche.

This book was supposed to come out a year ago. I'm not sure what the delay was, but now it's being released about the same time as the new Sibley which now contains illustrations of a lot of these same birds. The question is how many birders are going to get this book when the new Sibley covers most of them at least in passing. I think I've seen exactly 3 birds from the book in the ABA area and unless I move to SE Arizona my odds of discovering one on my own is close to nil. Unless you're birding the Alaskan islands, doing a lot of pelagics, or living in one of the border regions (or conceivably even California) this book is of academic interest, really nicely done, but may not have that much practical use. Off Amazon this book is $20-25, the dust jacket says $35. Honestly though, this book is certainly worth owning at that price even if my Midwestern readers are probably only going to be chasing (or dreaming) about these birds. If you've got a family of 4 you can't get out of Panera Bread without spending more that that.

Want others' opinions? Here's Cory Gregory and Jerry Jourdan.

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

the Crossley Hawk Guide

The initial Crossley ID guide promised a new approach to bird identification. It was a cool book, but I think the new Crossley Raptors book comes closer to this. It builds on the format that the main guide does though the more limited scope allows it much more freedom. There are 160 pages of plates which will appear familiar in format to those who have viewed the initial book. With only 34 species to cover though, each gets at minimum 2 full pages.

Following the initial 2 pages, most species then have plates dedicated to aging and plates that compare similar species. These are presented as unknowns with the images numbered with the answers in the back. I think that is the biggest innovation of this book. It functions more as a workbook than a Field Guide allowing for much more active learning than simply passive review of pics. I took a couple of the quizzes, I was right on the species of 2 of the accipiter plates about 90% of the time (I didn't try to age them). I'm not sure what to make of this, I have more difficulty ID'ing some of my own pics of accipiters in flight. I think this implies that Crossley hasn't just slapped in any photo that's sharp no matter the pose, rather I suspect he's chosen birds in poses that are fairly typical of the mental image of what these birds look like in flight.

The crispness of the photos are excellent. I estimate there are about 1000 images in this book, the overwhelming majority of which are original. I compared a couple of the common species accounts with the original Crossley East and didn't note any duplicates. With rarer species there are some more prominent duplicate images (one of the Gyrfalcons, a Caracara, the main Hook-billed Kite, one of the Bald Eagles). There are a couple situations where an image from the same series of shutter exposures of the same individual are used (at least one of the Goshawks and one of the Golden Eagle). That being said, there was much less replication of images than I had expected there to be.

The last 90 pages of the book are text descriptions at about the level of the Howell and Dunn Gulls book. They're not as technical as the Olsen and Larsson Gulls of North America, Europe, and Asia book or the Wheeler Raptors book. Each account begins with few paragraphs vaguely channeling a Pete Dunne essay that introduce the species, some are told first person from the bird's perspective, some are told in the 3rd person about the bird, and some are from the birder's perspective. Personally I would have kept the voice more constant but it's a minor point. There is an excellent prose description of the bird's flight style. I don't know that any book is going to be able to approach the venerable Dunne Sibley and Sutton Hawks in Flight in that regard, but these are very readable.

The other criticism I have of the book is that it includes only the regularly occurring species. While I know the line has to be drawn somewhere (there's little reason to include some of the relatively random single North American Red-footed Falcon or Collared (?) Forest-falcon records), but I would have included semi-regular birds like the 2 rare sea eagles or Hobby Falcon. Having been lucky enough to recently see the Lesser Sand-plover I was grateful that this species (as well as Greater) was included in the Obrien Crossley and Karlson Shorebird guide (which incidentally is the only other book on my shelf that presents a good number of birds as unknowns).

I would recommend this book. I don't know that I would use it as a field guide, there's not a lot of easy direct comparisons species to species, but it will help a person get a better feel for the birds so that if studied, you will need it a book in the field a lot less.

I think I'm going to start buying lottery tickets, it'd be a ton of fun to create the neo-tropical counterparts to these books.

The last 90 pages of the book are text descriptions at about the level of the Howell and Dunn Gulls book. They're not as technical as the Olsen and Larsson Gulls of North America, Europe, and Asia book or the Wheeler Raptors book. Each account begins with few paragraphs vaguely channeling a Pete Dunne essay that introduce the species, some are told first person from the bird's perspective, some are told in the 3rd person about the bird, and some are from the birder's perspective. Personally I would have kept the voice more constant but it's a minor point. There is an excellent prose description of the bird's flight style. I don't know that any book is going to be able to approach the venerable Dunne Sibley and Sutton Hawks in Flight in that regard, but these are very readable.

The other criticism I have of the book is that it includes only the regularly occurring species. While I know the line has to be drawn somewhere (there's little reason to include some of the relatively random single North American Red-footed Falcon or Collared (?) Forest-falcon records), but I would have included semi-regular birds like the 2 rare sea eagles or Hobby Falcon. Having been lucky enough to recently see the Lesser Sand-plover I was grateful that this species (as well as Greater) was included in the Obrien Crossley and Karlson Shorebird guide (which incidentally is the only other book on my shelf that presents a good number of birds as unknowns).

I would recommend this book. I don't know that I would use it as a field guide, there's not a lot of easy direct comparisons species to species, but it will help a person get a better feel for the birds so that if studied, you will need it a book in the field a lot less.

I think I'm going to start buying lottery tickets, it'd be a ton of fun to create the neo-tropical counterparts to these books.

Friday, April 12, 2013

The World's Rarest Birds

With my computer thoroughly crashed I'm going to fall back on a book review. I took advantage of Princeton Press's offer of a free review copy of one of their latest books, The World's Rarest Birds, an encyclopedic treatment of the world's endangered species.

The book has its origins in a photo contest run in Europe for rare birds that ultimately turned into this project, an attempt to depict most of the endangered birds of the world (here a cyclodes of some sort) apparently the only photo of it in existence:

The first 60 or so pages of this about 350 page near coffee-table sized book deal with the factors leading to population declines. Most of us are familiar with these, but it deals with them in-depth and gives some interesting specific examples (including of a starling species that's impressive enough that the captive breeding facility was broken into by gunmen to steal the birds for the cagebird trade).

The remainder of the book gives index card sized vignettes (4 to a page) about many of the endangered birds of the world. The title and the presentation imply that this is an exhaustive list. It may well be, but the determination of what's counted as endangered obviously varies. It ranges from birds that are almost certainly extinct through birds with populations in 6 figures like Marbled Murrelet. Kirtland's warbler gets a mention in one general paragraph about North American birds, but doesn't get the full vignette treatment that about 600 other birds receive; I found this surprising.

The book does lay out the reasoning behind not declaring birds like Ivory-billed Woodpecker or Eskimo Curlew extinct; I'm not sure that I totally agree with it, but the book does at least use the past tense in its treatment of many of these.

There are many impressive photos in the book, but I think that the impressiveness of many of them is based on their rarity. In a book of nothing but really rare birds this effect somewhat wears off. There's definitely a depressing aspect to this book; for many of us birding is a huge escape, reading about birds that are dying out (and there's clearly many many species that are), is somewhat sobering. I think that would have been helped somewhat by putting in some highlights of recovery programs that have worked as sidebar-type articles. It's also hard to put a lot of the birds in context. Just opening the book at random, I find vignettes about Apalis's, wood-hens, bushbirds, warbling-finches, crombecs; I've never heard of any of these. In some ways it's hard to get that emotionally invested in birds I've never heard of. That problem is probably one of the main goals of this book. If people are more aware of specific birds, or habitats that need protection then money will more likely be able to be raised.

At between $28 and $45 depending on the source, this is not a super-expensive book. I read a Steve Howell editorial once about birders' unwillingness to buy a book that they can review over and over when there's not a big difference between that number and a trip with the family to a restaurant that people wouldn't think twice about, and tend to agree with him. This is a worthwhile book to own and certainly has a ton of information in it.

Monday, August 1, 2011

the Crossley Guide

With the fall waterbird migration due to start accelerating hopefully my schedule will allow me to get out a little more. Now's probably a good time to squeeze in one more book review:

I have to admit, my first impression flipping through this book was "wow." There are a ton of high quality photos. My next thought was disappointment that the book only covered Eastern birds. As I flipped farther through, while the coverage map shows a Peterson-like definition of the Eastern U.S., the book really covers any place north of Arizona/New Mexico and east of the Rocky Mountains. Black Rosy-finch and Timberline Sparrow are probably the first Westerners to get dropped, though a lot of more western birds with regular vagrancy potential (e.g. Lewis's Woodpecker, Varied Thrush, etc) and even a good number of the Rio Grande rarities (e.g. Crimson-collared Grosbeak, Varied Bunting) are included as well. I think every bird on the Michigan checklist (including White-collared Swift!) is included.

I have to admit, my first impression flipping through this book was "wow." There are a ton of high quality photos. My next thought was disappointment that the book only covered Eastern birds. As I flipped farther through, while the coverage map shows a Peterson-like definition of the Eastern U.S., the book really covers any place north of Arizona/New Mexico and east of the Rocky Mountains. Black Rosy-finch and Timberline Sparrow are probably the first Westerners to get dropped, though a lot of more western birds with regular vagrancy potential (e.g. Lewis's Woodpecker, Varied Thrush, etc) and even a good number of the Rio Grande rarities (e.g. Crimson-collared Grosbeak, Varied Bunting) are included as well. I think every bird on the Michigan checklist (including White-collared Swift!) is included.The plates are photo essays of various images photo-shopped together. Here's the book fully opened to the teal (again don't take my photo of the photo as representative of the photo quality, this is to show the lay-out).

Crossley has attempted to depict the birds in usual postures in their habitat. My wife was particularly impressed by this, saying that this book would have been very helpful when she was starting out before she realized how tied down a bird was to its habitat. Some of these are really excellent, for example the Nelson's sparrow is in exactly one of the grasses we have found them in here in Berrien. Similarly the Common Goldeneye, Common Merg, and Bufflehead plate could just as easily have been taken at Tiscornia. The Phoebe plate could be a pic of my in-laws garden where they nest. Usually the backgrounds complement the pictures; there's some light-houses behind some and even a rainbow behind frozen Niagara for the Glaucous Gull. Occasionally the backgrounds can be distracting however (the phoebe plate for example has a random gentleman looking at the camera - unless that's the author's father I would have photo-shopped him out). I'm not sure I would have put the Ovenbird in a shady backyard or the Orchard Oriole in suburbia, but this may just reflect differences between New Jersey and Michigan, and for every plate where a person might quibble somewhat, there's many more that really look bang-on for habitat.

Crossley has attempted to depict the birds in usual postures in their habitat. My wife was particularly impressed by this, saying that this book would have been very helpful when she was starting out before she realized how tied down a bird was to its habitat. Some of these are really excellent, for example the Nelson's sparrow is in exactly one of the grasses we have found them in here in Berrien. Similarly the Common Goldeneye, Common Merg, and Bufflehead plate could just as easily have been taken at Tiscornia. The Phoebe plate could be a pic of my in-laws garden where they nest. Usually the backgrounds complement the pictures; there's some light-houses behind some and even a rainbow behind frozen Niagara for the Glaucous Gull. Occasionally the backgrounds can be distracting however (the phoebe plate for example has a random gentleman looking at the camera - unless that's the author's father I would have photo-shopped him out). I'm not sure I would have put the Ovenbird in a shady backyard or the Orchard Oriole in suburbia, but this may just reflect differences between New Jersey and Michigan, and for every plate where a person might quibble somewhat, there's many more that really look bang-on for habitat.

I certainly enjoy flipping through the pages and if Crossley can help inspire my kids to pick up the hobby this book will be a real coup. Five-year-old Hazel immediately wanted to color some of the birds on the page I was looking at (and it isn't even a really super-colorful page either), but here's her interpretation of the Connecticut Warbler (I drew the outline for her):

I certainly enjoy flipping through the pages and if Crossley can help inspire my kids to pick up the hobby this book will be a real coup. Five-year-old Hazel immediately wanted to color some of the birds on the page I was looking at (and it isn't even a really super-colorful page either), but here's her interpretation of the Connecticut Warbler (I drew the outline for her):

Crossley has attempted to depict the birds in usual postures in their habitat. My wife was particularly impressed by this, saying that this book would have been very helpful when she was starting out before she realized how tied down a bird was to its habitat. Some of these are really excellent, for example the Nelson's sparrow is in exactly one of the grasses we have found them in here in Berrien. Similarly the Common Goldeneye, Common Merg, and Bufflehead plate could just as easily have been taken at Tiscornia. The Phoebe plate could be a pic of my in-laws garden where they nest. Usually the backgrounds complement the pictures; there's some light-houses behind some and even a rainbow behind frozen Niagara for the Glaucous Gull. Occasionally the backgrounds can be distracting however (the phoebe plate for example has a random gentleman looking at the camera - unless that's the author's father I would have photo-shopped him out). I'm not sure I would have put the Ovenbird in a shady backyard or the Orchard Oriole in suburbia, but this may just reflect differences between New Jersey and Michigan, and for every plate where a person might quibble somewhat, there's many more that really look bang-on for habitat.

Crossley has attempted to depict the birds in usual postures in their habitat. My wife was particularly impressed by this, saying that this book would have been very helpful when she was starting out before she realized how tied down a bird was to its habitat. Some of these are really excellent, for example the Nelson's sparrow is in exactly one of the grasses we have found them in here in Berrien. Similarly the Common Goldeneye, Common Merg, and Bufflehead plate could just as easily have been taken at Tiscornia. The Phoebe plate could be a pic of my in-laws garden where they nest. Usually the backgrounds complement the pictures; there's some light-houses behind some and even a rainbow behind frozen Niagara for the Glaucous Gull. Occasionally the backgrounds can be distracting however (the phoebe plate for example has a random gentleman looking at the camera - unless that's the author's father I would have photo-shopped him out). I'm not sure I would have put the Ovenbird in a shady backyard or the Orchard Oriole in suburbia, but this may just reflect differences between New Jersey and Michigan, and for every plate where a person might quibble somewhat, there's many more that really look bang-on for habitat.The descriptions are short but generally good, including some pearls on finding Saw-whets or fall Connecticuts that I've not seen published before. They tend to be informal (describing anis as having a "whacking" big bill) though sometimes a bit over the top (do I need to read that a Swallow-tailed Kite could fit in the movie Avatar?). I think my reviewer when I was writing ID features for MBNH would have objected to me saying that Indigo Buntings "lack any purple tones," or that Eastern Meadowlarks "rarely" form roadside flocks in winter. In my experience, Indigo Buntings in some lights can have purple head gloss and if the roadsides are the only areas that have some exposed grass, then that's where the meadowlarks will gather (and I've made efforts to photograph the spread tail on these to try to make sure I'm not missing Westerns).

The Photo-shopping is generally very good, though initially when I was looking at the plates it took a little getting used to seeing birds in focus in multiple focal planes. Crossley writes in his intro that he tries to show all or nearly all plumages of a bird and indeed, there is a transitional plumage of late summer/early fall Black Tern that I hadn't seen photos of before. That being said, this book won't replace Sibley since there are plumages that aren't covered well. For example, there's an excellent photo of a juvenile Gull-billed Tern that led me to look over to the next plate, Sandwich Tern, to see what its juvie looks like. There isn't one pictured. Similarly, for Little Gull, there's no juvenile illustrated, and only a couple very distant shots of a full adult. Granted, sub-adults are what we encounter most frequently at Tiscornia, but I have seen both full juvie and full adult there as well.

I think I would have taken a somewhat different tack for the flight shots of the ducks. They really blend into the background. Crossley explains that he feels this is how things appear in real life. I would disagree. You generally see ducks flying either against the sky, or against the water. They don't spend a ton of time flying at an altitude with trees directly behind them, and if they are, then they're close enough to see well. I would have put more of the duck flight shots wing-on with a cleaner background. I like what he's done with shorebird flight shots, frequently the flock shape is pictured; these generally jive well with my experience of them, though I don't usually see 5 sanderling lined up perfectly in a row. I would have included more pics of the grassland birds, especially the Ammodramid sparrows, flying away. Some of this may have to do with the fact that the overwhelming majority of the (10,000??!!) images in the book are the author's own, very few are the work of other photographers. Soliciting a few more photos of specific species could have been helpful, to my eyes the 3 images of Baird's Sparrow are of the same individual.

In the frontpiece is about 14 pages of thumbnail sized pics of the regularly occurring birds that indexes to the full plates. A lot of these pics could have stood to be brightened.

Overall, though, this is an excellent and fun book. It is likely too big to be a field guide though. I think Crossley also could have departed slightly more often than he does from phylogenetic order to put more similar species together. He already departs from phylogenetic order since the rarities are grouped 2 or 4 to a page rather than having a full plate. Why not then make other subtle tweaks like re-ordering the swans to put Tundra and Trumpeter facing each other, move the mergansers to allow the eiders to face each other, etc?

I think that the person who will most benefit from it is a birder who is past the beginning stages who wants to look at a book at night to improve his/her pattern recognition; having the habitats behind the bird will certainly help this process to put a bird into context. There is, though, something for everyone. I would, for example, ask that whichever of the bird committee members who objected to my description of a putative Ross's goose's bill base as "irregularly vertical" to describe the close-up of the bird in the lower left hand corner.

I certainly enjoy flipping through the pages and if Crossley can help inspire my kids to pick up the hobby this book will be a real coup. Five-year-old Hazel immediately wanted to color some of the birds on the page I was looking at (and it isn't even a really super-colorful page either), but here's her interpretation of the Connecticut Warbler (I drew the outline for her):

I certainly enjoy flipping through the pages and if Crossley can help inspire my kids to pick up the hobby this book will be a real coup. Five-year-old Hazel immediately wanted to color some of the birds on the page I was looking at (and it isn't even a really super-colorful page either), but here's her interpretation of the Connecticut Warbler (I drew the outline for her):Saturday, July 2, 2011

A change of pace

Presenting, a new feature to this blog, Book Reviews! In a new marketing device, Princeton Press is sending free copies of some of their books to bloggers with the agreement we'll review them. I'll leave it for you to decide if that has affected my objectivity. That being said, I think that Liguori's Hawks at a Distance is an excellent book.

The introduction is well done overall, I think that one of his primary points is to emphasize shape rather than exact plumage marks since he points out that it's easy to get hung up in minutiae and apply field marks to ages or color morphs to which they do not apply. One of the follow-up concepts is to spend more time watching the bird with bins and less time with the scope. In the introduction I would have been more specific in the photography sub-section about how settings need to be tweaked for photography of distant raptors. Specifically, an image needs to be over-exposed to avoid the camera's computer from reducing the image to a black dot on a pretty medium blue field. Doing this requires some combination of increasing the ISO, reducing shutter speed, and lowering the F stop (the trade-offs of these being increased graininess, possibly decreased clarity, and decreased depth of field respectively).

The species focused upon are migrants, generally those expected regularly (or at least annually) at Eastern hawkwatches. Therefore, the species with full accounts are the 3 accipiters; the common Eastern buteos plus regular rarities Swainson's and Ferruginous; Harrier; the 3 common falcons plus Prairie; as well as Osprey, the 2 eagles and the 2 vultures. Gyrfalcon, Mississippi Kite, and California Condor (!) are treated more briefly with even briefer discussions of Short-tailed Hawk, Zone-tailed Hawk, White-tailed Hawk, White-tailed and Hook-billed Kite, and Caracara. Personally I would have liked a little more info on Short-tailed Hawk. If you're going to include Zone-tailed Hawk and Condor I'm not sure why you wouldn't throw in a little bit on Black-hawks as well. Since this book focuses on birds encountered at hawkwatches, I probably would have added additional shots of Short-eared Owl (there's one along with 2 Hawk Owl shots).

There are no illustrations of perched hawks.

The full-frame eye-candy shots that lead each section range from decent to stunning. Ironically while an excellent shot of Red-shouldered is the cover bird, the Red-shouldered image that leads the species account is to me clearly the weakest of this format. I was disappointed when I reached the Gyrfalcon section to find it missing the lead-off portrait like the swooping immature Goshawk or dramatic young Swainson's that lead their respective accounts.

The (usually) one page section of prose describing each species is well written and is far closer to the conversational style of Pete Dunne in the classic "Hawks in Flight" than the highly dry, densely technical flavor of Wheeler's "Raptors." It comes pre-highlighted with key points in bold. I found it interesting that he bold-faces (on page 25) that "the underside plumage is often not useful in identifying distant juvenile accipiters." Dunne, in Hawks in Flight (page 72) italicizes that "if an immature accipiter appears white below, it can safely be called a Cooper's" in his section summarizing accipiter separation.

The meat and potatoes of this book follow the one page description with plates featuring (usually) 6 photos per page of distant hawks in flight. Here's one of the 6 photos on one of the gyrfalcon plates (please don't take these photos I took of the photos to be illustrative of the photo quality in the book, rather examples of the style) that caught my eye as familiar:

The same photo is used in Wheeler's "Raptors," cropped very differently (his book is laid out 4 photos to the page):

The same photo is used in Wheeler's "Raptors," cropped very differently (his book is laid out 4 photos to the page): Ligouri emphasizes that he wants to show the photographs as you would see the birds in the field through binoculars so isn't showing close-up views. That being said, I would have cropped them in by at least 10-20%, but I tend to over-crop my photos. This was the only photo that stood out to me as looking familiar. Over 95% of the (~550) color photos are Ligouri's own. I haven't studied every species account, but did look over a couple of them fairly closely. I am not very familiar with Goshawk, having seen only about 4 birds flying by briefly so I studied those plates fairly closely. It does definitely give a sense of a different bird, with much broader secondaries than a Coop and a much shorter hand than a buteo; the proof will be this fall if one jumps out at me more quickly. The Red-tailed Hawk section is the longest (expectedly so with the number of subspecies). In this section there are 6 shots of Eastern, 23 of Western, 27 of Harlan's, 4 of Kriders, and 18 unidentified to subspecies. The number of un-ID'd birds goes along with a lot of the cautions in the text that a lot of distant birds need to be left as Redtails. Many of the un-ID'd photos make general points about the substantial effects of lighting, age, or both, on appearance.

Ligouri emphasizes that he wants to show the photographs as you would see the birds in the field through binoculars so isn't showing close-up views. That being said, I would have cropped them in by at least 10-20%, but I tend to over-crop my photos. This was the only photo that stood out to me as looking familiar. Over 95% of the (~550) color photos are Ligouri's own. I haven't studied every species account, but did look over a couple of them fairly closely. I am not very familiar with Goshawk, having seen only about 4 birds flying by briefly so I studied those plates fairly closely. It does definitely give a sense of a different bird, with much broader secondaries than a Coop and a much shorter hand than a buteo; the proof will be this fall if one jumps out at me more quickly. The Red-tailed Hawk section is the longest (expectedly so with the number of subspecies). In this section there are 6 shots of Eastern, 23 of Western, 27 of Harlan's, 4 of Kriders, and 18 unidentified to subspecies. The number of un-ID'd birds goes along with a lot of the cautions in the text that a lot of distant birds need to be left as Redtails. Many of the un-ID'd photos make general points about the substantial effects of lighting, age, or both, on appearance. The final section of the book contains montage plates of hawks cruising and soaring to and fro from different angles, here's the Swainson's plate, you can compare it to the Swainson's photos from this spring.

Overall, this is an excellent book. The technological improvements in photography and printing made since Hawks in Flight was written 20+years ago allows the photos of Liguori's Hawks at a Distance book to blow the doors off of those in Hawks in Flight (not that the classic isn't still a good read or that Sibley's illustrations aren't still superb). At about $20 with tax I think this book is well worth the money to someone looking to spend time at hawkwatches, or someone who has spent reasonable amounts of time, but would like to improve their ability to pull out one of the rarer species.

Want another opinion and some more info on the book? Here's what Cory Gregory wrote about the book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)